The Christenot Mill, located at the head of Spring Gulch at Union City, Montana, began operation in 1867 to process gold ore from the nearby Oro Cache claim.

- May 26, 1863 – Gold discovered in Alder Gulch.

- 1863 – Benjamin Christenot records claims in the Summit District.

- 1865 – Montana Gold & Silver Mining Company incorporated.

- 1867 – Mill begins crushing Oro Cache ore.

- 1869 – Sheriff’s Sale of Mill.

- 1930 – Newspaper Article mentions the Christenot Mill.

- 1990 – Mill Site Surveyed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

- 1992 – Mill Encountered by Christenot descendant.

- 1995 – Christenot Family Reunion tour of Mill.

- 1997 – Stabilization plan developed by BLM. First work party with Christenots.

- 1999 – National Record of Historical Places.

- Current – Occasional Work Parties and Family Reunions.

Gold and Alder Gulch, Montana

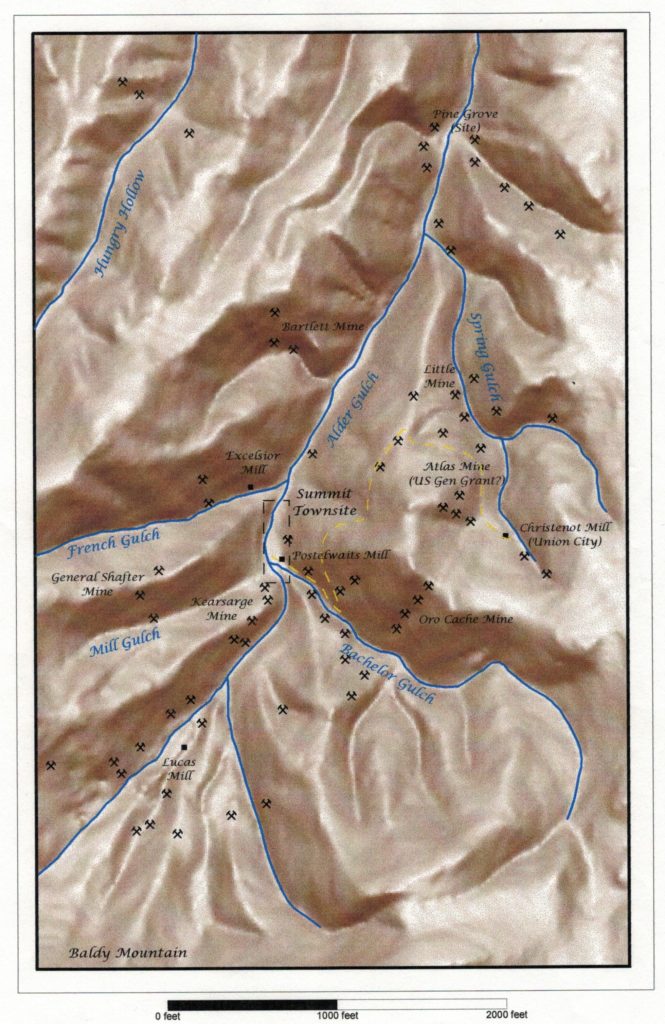

The first gold was discovered along Alder Creek in Alder Gulch on May 26, 1863. Alder Creek is a tributary of the Ruby River, in central Madison County, Montana. Alder Gulch sits north and below Baldy Mountain (9,600 feet), and nominally begins near the former small mining town of Summit City (7,000 feet). Often called the “Fourteen-Mile City” for the numerous settlements along the way, Alder Gulch trends north then northwest and settles at 5,121 feet at the town of Alder. Virginia City, once the territorial capital with a population of 5,000 in 1864, is half-way along the gulch between Summit City and Alder.

The Christenot Mill at Union City (7,560 feet) was built at the head of Spring Gulch, east of Summit City. The remains of the Christenot Mill provide a window of understanding for hard rock gold mining in Alder Gulch. Researching the history of this gold mill has provided much information.

Two questions come to mind: “What is the Christenot Mill, and what makes it so significant in Alder Gulch mining history?” Many gold mills operated in Alder Gulch beginning in the 1860s, and remains of several mill buildings still exist. The Christenot Mill, however, is the only Alder Gulch mill site that is listed on the National Historic Register.

Gold Mining in Alder Gulch

Placer Mining: Early gold discoveries were usually found by placer mining. Placer deposits of gold are nuggets and small particles that were separated from rock over eons of time by forces of nature and settled along streams and channels. The simplest method is to wash gravels using pans to separate heavy gold from the surrounding sediment. Along Alder Gulch, miners used pans, sluice boxes, rockers, hydraulics, and dredges; all using water to help separate gold from wherever it had been deposited. Miners would know that the source of the gold would be nearby. As placer deposits became worked out, many looked to the hills for the mother lode. Frozen conditions in the water at winter would also cause the miners to work elsewhere.

Lode Mining: Gold that remains in rock, such as quartz, exists in veins or lodes in the ground. Obtaining this gold is called lode or hard rock mining. These lodes are found on hills and mountain sides that are usually dry. Holes must be dug and the ore removed. Ore is rock or sediment that contains valuable minerals, and in the Alder Gulch area was formed predominately with quartz. This quartz ore has to be crushed, to separate the gold, at a mill. Water is required for gold milling, and hauling ore to a gold crusher (gold mill) was expensive and time consuming. A primitive way to crush or mill the ore was with an arastra. Bigger mills, typically stamp mills, would be more efficient and allow more ore to be crushed than a simple arastra. Large crushing mills would be needed.

When gold is found in amounts worth mining, the miner would stake the claim by marking the area and filing a claim with the local authorities. The first claim in a valuable area was called the discovery claim, and subsequent claims would be numbered after it, starting with #2, and physically described in relation to it.

Mine Districts and Mill Sites

A large area of mining activity would be formed as a mining district, with rules and regulations created by the miners. Within the mining districts, ideal mill sites would be identified. Miners understood the need to have crushing mills near water, and as close to the mines as possible. In addition to registering gold claims, groups of miners would also file claims on a mill site near a water source on which a mill could be constructed. The Christenot Mill was a result of this need. The land under Christenot Mill was not patented and thus remains under the ownership of the United States and assigned to the Bureau of Land Management.

Ideally, mills would also be sited near gold claims, and if possible at a lower elevation. Hauling heavy ore down the hill with the help of gravity is much preferred over hauling it up. Ore hauling in the 1860s was usually by wagons pulled by oxen, horses, or mules. It could also be sacked and carried on the backs of horses or mules.

It takes money, typically from investors, to fund costs for building a mill. Investors had to be convinced that miners had valuable gold-bearing claims that would produce enough gold to pay for mining and milling as well as a good return on capital invested.

Benjamin Franklin Christenot and the Oro Cache

Our Christenot relative, Benjamin Franklin Christenot was an early miner in Alder Gulch. He recorded claims #5 & #6 on November 5, 1863, from the discovery claim of a placer deposit in Alder Creek. On April 20, 1864, he recorded claim #2 southwest from the discovery claim on the Oro Cache, a lode deposit. These claims were in the Summit Mining District at the head of Alder Gulch.

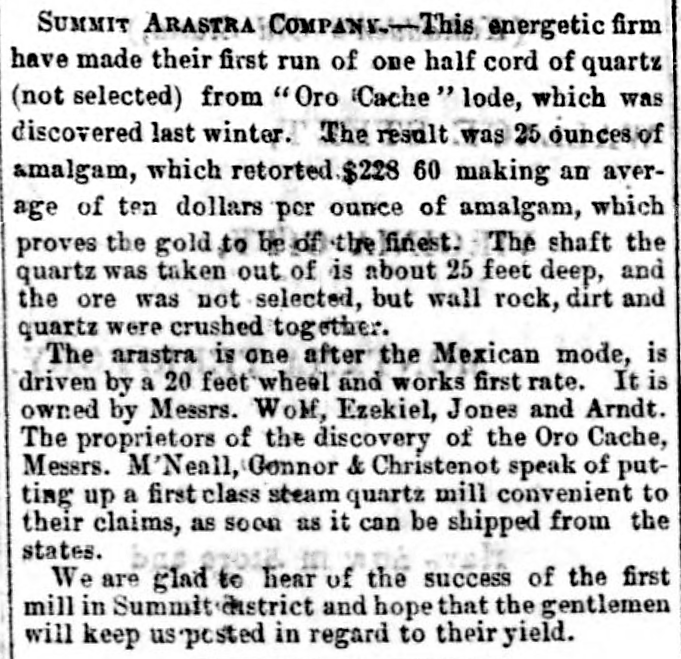

The Oro Cache, which sits atop of a hill just north of Mount Baldy, was one of the first gold-bearing quartz veins discovered in Summit District. It became one of the most productive gold properties in Alder Gulch. The methods of removing gold from lode or “hard rock” mining are different from placer mining. Hard rock mining of the gold from the Oro Cache first involved a primitive form of crushing known as an arastra.

On October 15, 1864, The Montana Post reported that the Summit Arastra Company milled some Oro Cache ore, and found it to be rich. Discussions were reported of “putting up a first class steam quartz mill convenience to their claims, as soon as it can be shipped from the states.” (“Summit Arastra Company,” 1864). In December of 1864, Benjamin Christenot commenced work on his Oro Cache claims using one mule to operate an arastra. He earned $8,358. This work in winter must have been difficult as the shaft of the Oro Cache sits at 8,040 feet of elevation.

With this start in hard rock mining, Benjamin was able to amass some 87 lode mining properties that were attractive to investors from the Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, area. Those investors formed the Montana Gold and Silver Mining Company (MGSM) which was chartered by the Pennsylvania Legislature on January 21, 1865. This money was used to build what became known as the Christenot Mill. (Prospectus, 1866.)

in 1866.

Construction and Operation of the Christenot Mill

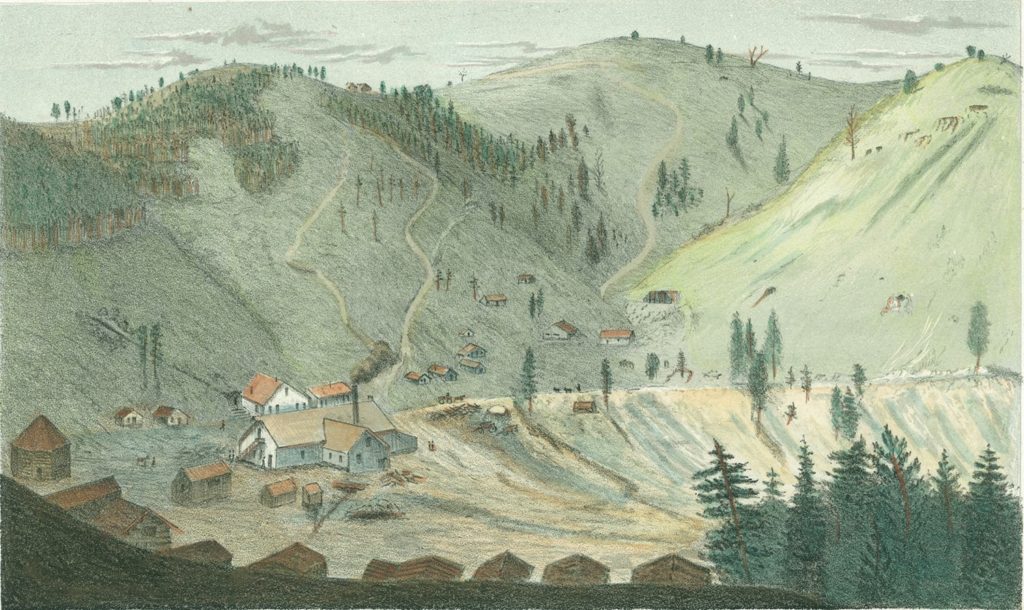

It took more than a year to build a building and transport milling machinery. On October 4, 1866, a wagon train funded by the Montana Gold and Silver Mining Company arrived at the mill and installation of machinery began. The Christenot Mill produced the first gold at the end of January 1867. It was the only Alder Gulch mill to utilize Chilian Roller crushers in the 1860s.

Several newspaper stories in the Montana Post, and descriptions by others in books provide construction and operation information about the Christenot Mill. (Miller, 1989/Tuttle, 1906)

Mill operation was typical to those around the world, in that the process-flow was gravity based. Heavy, uncrushed ore is introduced at the highest point, and progresses toward lower levels using the aid of gravity. In this case, the primary ore came from the Oro Cache, about 500 feet elevation above the mill, and was hauled down to the south side of the mill. An early photo shows openings in the now collapsed walls. Just inside of the mill building’s south wall are 4 separate wooden platforms with bolts that held Chilian roller crushing machines. Ore was likely dumped outside on the ground, and then workers used wheelbarrows to bring ore into the mill which was then shoveled or dumped into one of 4 crushers. The crushers were powered from overhead belting from the steam engine room that sits to the north of the crushers. Two large, heavy crusher wheels turned in a circular pan of about 5 feet in diameter. Ore was both crushed and ground by the short turning radius of the wheels.

Crushed ore was then removed and placed into one of 4 barrel amalgamators that were horizontally placed in timber frames that look like peninsulas projecting north from each crusher. Mercury was introduced, and likely iron balls inside the barrels, further crushed the ore. The mixture or amalgam was then poured onto copper-covered tables that sloped to the north. This amalgam must have been retorted or heated to drive off the mercury. Since this a deadly gas, the mixture was likely taken outside. A small furnace site appears to sit near the south east corner of the mill. Mercury was recovered for reuse, and the gold was stored in the vault in the south west corner of the “office”.

During the months of operation, the Montana Post noted several deposits of gold in the Nolan and Weary Bank in Virginia City from the Christenot Mill. (In Bank, 1867)

Union City

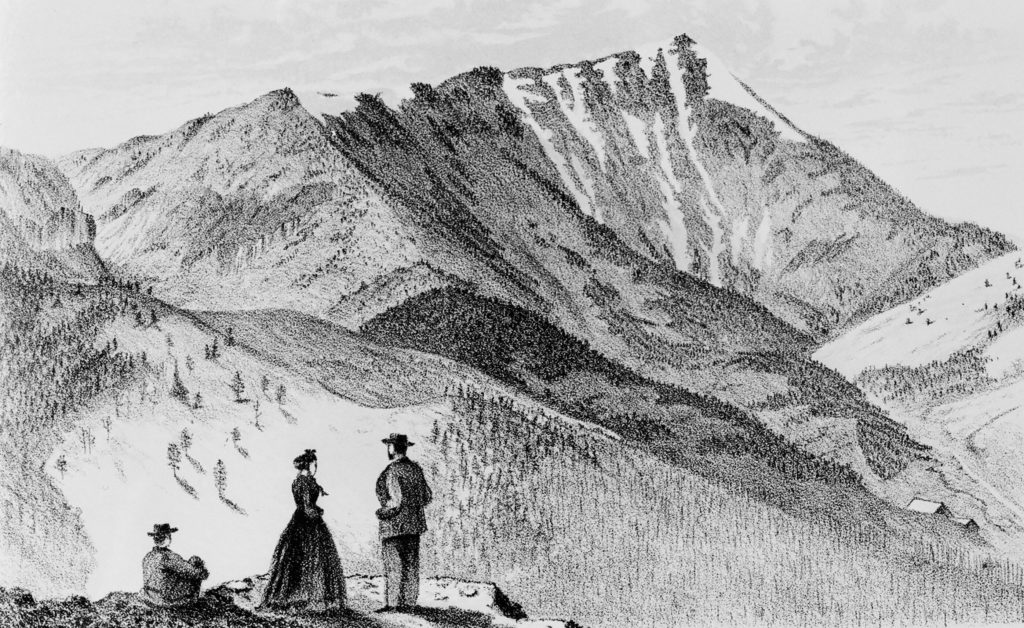

Another A.E. Mathews sketch shows Union City, the location of the Mill. This village, thought to be the earliest documented company town in Montana, consists of the Christenot Mill, houses for workers, and buildings used to support the operation of the Mill. The only items for sale in the company storeroom were goods and services needed in the operation of the Mill, such as gloves. The closest town where the workers and their families could shop for their needs was Summit, two miles to the west. The largest town of Virginia City was about 7 miles away.

This sketch shows three haulage roads coming down to the Mill from the Oro Cache above. Remnants of these roads still exist on the hill, but are covered with many downed trees from the once-again forested hill side.

Mentioned in the text that accompanied A. E. Mathew’s sketch of Union City, Montana, in his book, Pencil Sketches of Montana, is the “Stinking Water Valley” which was later known as the Ruby River Valley. See text below:

UNION CITY.

PLATE IV

UNION CITY consists of the Union City Mill and the dwellings of the Agent and miners in the employ of the company. It is charmingly located in a ravine far up on the mountain’s side and commands a fine view of the Great Rocky Range beyond Bannock, more than a hundred miles distant: and also a beautiful view of the Stinking Water Valley and Mountains, shown in Plate II. The dense forests of pine on this range have from here a velvet-like appearance.

In this plate, Grant Hill is seen on the right, and the Oro Cache Hill on the left and centre. The shaft house over the Oro Cache mine is seen on top of the hill in the centre of the picture. The road extending around Grant Hill from the mill is the road to Summit City, which lies on the opposite side of the hill.

A.K. McClure describes Union City in his book “Three Thousand Miles Through the Rocky Mountains.” He, his wife, and son spent the summer and fall of 1867 there. Upon his arrival, he assumed the manager or superintendent’s position of operating the mill from Benjamin Christenot. (Thomas Creigh became the superintendent after McClure left in January of 1868.)

There were several people that lived at Union City. The Mathews sketch shows various cabins, including several cabin roofs in the foreground. Benjamin, as first Superintendent lived in the manager’s house which appears to be the building just south of the mill. Records show that he sold the manager’s house to McClure.

The Thomas Creigh Bozeman Trail Diary, as well as family stories, verify that several Christenot family members related to Benjamin came to Union City. Since they worked at the mill it is likely they lived nearby. Those known to have been there are Charles (younger brother to Benjamin by 4 years), his wife Martha (Craig) Wilton Christenot, and Martha’s daughter Alice May Wilton. Frederick Christenot (father of Benjamin and Charles) and his second wife Margaret were also there and lent money to MGSM. Hattie Christenot, first child of Charles and Martha was born in March of 1867. It is likely she was born in Union City, but perhaps she was born in Virginia City.

Mill Failure

The choice of citing the Mill near the Oro Cache was sound, but operation of the Mill was short lived. The first ores from lode mines of that era produced gold that was freed from rocks due to oxidation and weathering over eons of time. This type of ore could be milled with minimal, primitive crushing and amalgamation. Once this near-surface ore was processed gold milling techniques such as cyanidation were required to remove gold from the rock. Such advanced processes were not used in Alder Gulch until around 1900. There was not enough oxidized ore from the Oro Cache and other lodes to sustain operation. Short term loans to MGSM were made to keep the operation going, but they could not be repaid, and foreclosure took place. (Oro Cache ore was abundant, and was extracted and milled as late as the 1930s, having been hauled to smelters in Anaconda.)

It was not long before the Mill failed. A Sheriff’s Sale was ordered for July 8, 1869. Those working there moved on. Christenot family members were soon living at Puller Springs, and at Home Park. Charles and Martha eventually had nine children. All but one reached maturity and married, thus spreading Christenot descendants throughout Montana and the northwest. Benjamin Christenot mined at a mill near Brown’s Gulch and eventually settled in California.

Rediscovery of the Mill

Over time the knowledge of the Christenot Mill and Union City faded from memories of most family descendants. An exception to this was the sharing of a newspaper story written by Lew L. Callaway about Union City. (Calloway, 1930). A clipping of this story was sent by Anna (Christenot) Swisher, daughter of Charles and Martha, to Alene (Counter) Thurber, a great granddaughter of Charles and Martha. This clipping was saved and handed down to younger descendants.

In September of 1992, Christenot descendant Nick Shrauger, his wife Betty, and daughter Donika participated in a horseback poker ride south of Virginia City. One of the stops included the Christenot Mill which was unknown to them. Two years later, with the aid of the 1930 Madisonian newspaper clipping, Nick verified with John Ellingsen and Matt Stiles the Christenot family’s involvement with the stone mill building he first visited on the poker ride.

Mill Stabilization

Gwen (Christenot) Henderson, with her brothers Gale and George Christenot, hosted a Christenot Family Reunion in Bozeman in 1995. One of the activities was a guided trip to the Christenot Mill. Family members were inspired from what they learned of their family history at Union City. This led to a 1997 volunteer work party of family members and friends to aid the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in fencing and stabilizing the mill building. As a result of this experience, the Christenot Mill Preservation Association was formed to partner with the BLM. This working partnership still continues. The Stabilization Plan for the Christenot Mill (24MA1215) was produced by the BLM in 1997.

On February 26, 1999, the National Register of Historic Places recognized Union City (site of the Christenot Mill) of Madison County, Montana. The National Registration plaque in front of the remains of the Mill building helps educate visitors as to the importance of this site.

Family Legacy

The greatest legacy of the Christenot Mill is uniting of the Christenot family and preserving a unique feature of hard rock mining in Alder Gulch. Reunions of the extensive Christenot family have been held every three years since 1995. With the BLM, Christenot family and friends hold work parties every few years to help preserve and stabilize the Christenot Mill.

References

Backus, P. (1997, July 13). The Forgotten Union City. The Montana Standard.

Barsness, L. (1962). Gold Camp, Alder Gulch and Virginia City (First Edition). Hastings House.

Callaway, L. L. (1930, October 10). Tales of Alder Gulch. The Madisonian.

Creigh, T. (2000). Thomas Alfred Creigh Diary. In S. B. Doyle, Journeys to the Land of Gold (p. 688). Montana Historical Society Press.

In Bank. (1867, April 20). Montana Post.

Lode Mining in Summit District. (1865, March 25). Montana Post.

Lovell. (1867, August 17). Oro Cache Lode – Oro Cache Discovery. Montana Post.

Mathews, A. E. (1868). Pencil Sketches of Montana. New York – The Author.

McClure, A. K. (1869). Three Thousand Miles Through the Rocky Mountains (First Edition). J.B. Lippincott & Co.

Meyerriecks, W. (2003). Drills and Mills (Second Edition).

Miller, J. K. P. (1989). The Road to Virginia City: The Diary of James Knox Polk Miller (pp. 107–109). University of Oklahoma Press.

Mining Matters. (1867, July 27). Montana Poster.

Pace, D. (1962). Golden Gulch (First Edition). McKee Printing Co.

Parrett, A. (2018). Images of the West: Alfred Mathews. Big Sky Journal.

Phillips, P. C., & Partoll, A. J. (1951). Montana Reminiscences of Isaac I. Lewis. The Montana Magazine of History.

Prospectus: The Montana Gold and Silver Mining Company, (1866), Leisenring’s Publishing House, Philadelphia.

Russell, W. H. (1953). A Biography of Alexander K. McClure [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Wisconsin.

Sant, M. B. (1997). Stabilization Plan for the Christenot Mill (24MA1215). Bureau of Land Management.

Shrauger, N. (1998a). Union City. Montan Ghost Town Quarterly.

Shrauger, N. (1998b). The Christenot Mill at Union City. Montana Ghost Town Quarterly.

Shrauger, N. (2001). Christenot Family. In L. Wostrel, Dreams Across the Divide (p. 112). Stoneydale Press Publishing Company.

Summit Arastra Company. (1864, October 15). Montana Post.

Tuttle, D. S. (1906). Reminiscences of a Missionary Bishop (First Edition, pp. 137–139). Thomas Whittaker, New York.

Research

Written by Nick Shrauger and Andrea Surfleet. More information, photographs, and documents about the Christenot Mill are available and will be added over time. Our research is based on the sources listed and the long-time study of the Mill by Nick Shrauger.

Please contact us with additions, questions or corrections. Last updated March 2022.

Christenot Mill Preservation Association

Read more about endeavours to stabilize the Mill site at the page for Christenot Mill Work Parties.